Guest posting: Dr Eliza Milliken, Infectious Diseases Physician, Clinical Pharmacology Fellow, Chair District Quality Use of Medicines, Hunter New England Health

Key takeaways

- Antibiotics are selective chemotherapeutic agents—cytotoxic to bacteria, not humans

- Antibiotic efficacy is governed by a complex interplay of host pharmacokinetics and organism pharmacodynamics

- It’s not just about T>MIC or half-life—dosing needs context

- Critically ill patients often need higher, more frequent dosing due to altered PK and higher bacterial loads

- Oral switch when clinically appropriate is effective, cost-saving, and improves the patient experience

- Don’t forget the immune system—antibiotics inhibit bacterial growth, but it’s the host that clears the infection

Antibiotics are chemotherapy

Surprisingly, the term chemotherapy was first coined in relation to antibiotics, not cancer treatments. Antimicrobials are selectively cytotoxic—not to human cells, but to microbial cells. This includes bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and even helminths. But for this post, we’ll focus on antibacterials.

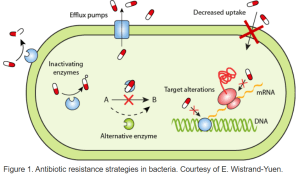

The perfect antibiotic would selectively target bacterial cells without interacting with human cells. While pharmacokinetics (what the body does to the drug) are host-dependent, pharmacodynamics (what the drug does to the bug) are determined entirely by the bacteria—at least in theory. In reality, there’s one key human organ we often overlook: the microbiome. Disruption of this “forgotten organ” explains many adverse effects of antibiotics.

How Antibiotics Work: Mechanisms and Spectrum

To understand how antibiotics work, let’s quickly revisit bacterial structure. Bacteria are prokaryotes—cells without nuclei. They’re surrounded by a peptidoglycan mesh, which holds their contents under osmotic pressure. Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., staph, strep) have thick mesh layers; gram-negatives have thin ones but have an additional layer of lipopolysaccharide. The bacterial envelope—comprising the cell wall and plasma membrane—regulates permeability and survival. Antibiotics act either by disrupting the peptidoglycan layer or by interfering with internal bacterial metabolism.

The target of the antibiotic determines its spectrum—the types of bacteria it can kill. Key antibiotic targets include:

For example, beta lactam antibiotics replace some of the usual proteins in the peptidoglycan layer; one this “mesh bag” layer is weakened, bacteria with strong internal osmotic pressure (i.e. Gram positive bacteria) will explode and die (lyse)! This is why many of the beta lactam antibiotics (especially earlier generations) and antibiotics that target the peptidoglycan layer in general are mostly effective against Gram positive organisms. Gram negative organisms in general terms are less susceptible to these types of antibiotics. Antibiotics that target internal metabolic processes and protein synthesis are more likely to be effective.

Gram negative anaerobic bacterial species (e.g. Bacteroides fragilis group) usually produce class A betalactamases and are resistant to penicillins and most cephalosporins; susceptibility can be restored with a betalactamase inhibitor like clavulanate or tazobactam. Conversely, Gram positive anaerobic bacterial species are usually susceptible to penicillins, cephalosporins and glycopeptides (vancomycin).

Choosing the Right Antibiotic

When faced with multiple options (e.g., MSSA treatable by penicillins, cephalosporins, or carbapenems), how do you choose?

General Principles:

– Target the specific pathogen

– Ensure penetration to the site of infection

– Use the narrowest spectrum possible

– Choose the widest therapeutic window

– Prefer drugs that are available, affordable, and easy to give

Choosing wisely requires understanding three core factors:

– Pathogen: What is its MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration)?

– Host: Can the patient absorb, distribute, and metabolise the drug?

– Drug: Will it reach the necessary concentration at the infection site?

MIC, PK, and PD – What Really Matters?

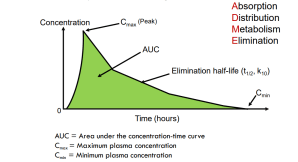

The mean inhibitory concentration (MIC) in simple terms is the drug concentration in a fluid at which the replication of an organism will be stopped. You often hear about the MIC 50; that is the drug concentration at which there is a 50% reduction in organism reproduction. The MIC90 means a 90% reduction and so on. However, this is just a starting point.

To be effective, a drug must reach the site of infection at a sufficient concentration for a sufficient duration. If the patient has meningitis will the blood concentration be sufficient for the drug to cross the blood brain barrier in an adequate amount? And so on.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) “PK is what the body does to the drug”

- Barriers like the blood-brain barrier or poor GI absorption matter

- In critical illness: hypoalbuminemia, altered VoD, renal dysfunction

Pharmacodynamics (PD) “PD describes the critical interaction between drug and bug”

- Antimicrobial effect (linking drug PK and MIC)

- Toxicity (toxicodynamics)

The Three PK/PD Patterns of Antibiotic Efficacy

Pattern 1: Concentration-dependent killing +long post-antibiotic effect (PAE)

Cmax/MIC or AUC/MIC is the efficacy measure (various targets)

- Higher concentrations = better killing

- Example: Aminoglycosides, Daptomycin

Pattern 2: Time-dependent killing, minimal PAE

T>MIC is efficacy measure (target of > 50% of the 24 hrs is usually sufficient)

- Higher concentrations don’t help

- example: Beta-lactams

Pattern 3: Time-dependent killing + prolonged PAE

AUC/MIC is the efficacy measure (various targets)

- Higher concentrations prolong suppression

- Examples: Azithromycin, Tetracyclines, Clindamycin

Patient-drug-organism nexus (reference McKinnon PS et al, 2004):

Other PK/PD Considerations Every JMO Should Know

Bioavailability and Route of Administration

When treating infections—especially in the context of sepsis—getting therapeutic levels of antibiotics into the bloodstream quickly is key.

- In sepsis, your goal is rapid systemic availability.

- IV administration offers predictable and sufficient plasma concentrations for high bacterial loads.

- That said, oral bioavailability can often be surprisingly good.

- Trials like POET and OVIVA have shown oral therapy can be just as effective once a patient stabilises.

- The pharmacodynamics of both time-dependent and concentration-dependent antibiotics can be optimised via the right route.

- In stable patients, oral is the new IV—don’t underestimate the power of the pill.

Tissue Penetration (Volume of Distribution)

Just because a drug reaches the bloodstream doesn’t mean it reaches the infection.

- Serum levels ≠ site levels. Drug must penetrate the infected tissue.

- Penetration depends on factors like:

- Passive diffusion

- Active transport

- Lipid solubility

- Protein binding

- CNS infections? Lipid solubility determines whether a drug can cross the blood-brain barrier.

- Intracellular bugs? You’ll want something that can get inside cells—macrolides, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones are good for atypicals (e.g. in community-acquired pneumonia).

PK Variability in Critical Illness

Critical illness can dramatically alter a drug’s pharmacokinetics. Be alert to these changes in ICU, trauma, or complex medical patients:

- Conditions like burns, spinal cord injury, obesity, pregnancy, and cystic fibrosis all affect drug handling.

- Renal dysfunction is the most common reason we adjust antibiotic dosing.

- Hepatic impairment makes drug metabolism harder to predict.

- GI dysfunction or hypoperfusion affects oral absorption and delivery to infection sites.

- Hypervolemia increases volume of distribution, often resulting in lower serum concentrations.

- Hypoalbuminaemia increases the free (active) drug fraction, which can lead to both enhanced clearance and toxicity.

- In many ICU patients, continuous infusions of beta-lactams are more effective at maintaining AUC and T>MIC.

CRP and CYP Inhibition: The Hidden Link

Most people don’t realise that elevated CRP can affect drug metabolism.

A retrospective study of 128 patients found that systemic inflammation significantly increases voriconazole levels, independent of dose.

- For every 1 mg/L increase in CRP, voriconazole trough levels rose by 0.015 mg/L (p < 0.001).

- Doses were consistent across patients—so inflammation, not dose, drove the levels.

- Likely explanation: Inflammation downregulates CYP450 enzymes (especially 2C19, 3A4, and 2C9), reducing drug clearance.

Clinical pearl: If your patient has a very high CRP their pharmacokinetics are likely altered by inflammation. Consider this if you are not getting the response you expect, especially for hepatically metabolised drugs.